Down-Sized Living in a Modern Age

In the summer of 1999 I suddenly found myself without a job or home. With a partner and newborn—and plenty of crazy ideas common to twenty-somethings—I decided to build a yurt and embark on homesteading in my native New Hampshire. Fifteen years later, I’ve learned most crazy ideas don’t work, but yurts are among the ones that work for me. I now build for folks full-time, primarily year-round yurts for other twenty-somethings starting out on similar paths. But I also construct lighter three-season yurts and ones used for studios, guest quarters, getaways, apprentice housing, and camping.

Yurt Life: Rustic Comfort

There are many ways people live in yurts. Some commute to real jobs every day. Others escape to the yurt for a few weeks in the summer, or turn to a backyard yurt for a few nights a week. For me, yurt living with four people (two of them quite young) meant day and night, summer and winter. That’s not to say we spent 24 hours a day within the bounds of a 20-foot circle. The yurt became just one of the rooms in our “house”—the others included the barnyard, shop, field, and woods. The yurt was simply the room we knew was always warm, dry, bug-free, and lit at night. Whether the yurt created my way of life or the other way round, I’ve never quite figured it out.

Yurt living and homesteading in general is profoundly place-specific. Despite its origins in central Asia—an area with dry climate and flat unforested steppes—a yurt works relatively well in rural New England. By comparison, the tipi is harder to heat in winter because the high cone funnels heat out and lets the rain in. Wigwams and earth lodges are a bit rustic even for those of us willing to rough it. Camper trailers leave something to be desired in the “soul” department. A yurt, on the other hand, is nice enough to spend a few years in while creating a forever home, but not so comfy that the house never gets completed.

Heating: Or How Not to Freeze

The first question I’m always asked is, “How do you stay warm in New Hampshire winters?” Answer: In a T-shirt with an airtight woodstove and two to three cords of dry firewood. In a 20-foot yurt (the size I know best), you’re never more than seven or so feet from the central stove. Putting the stove in the center heats the yurt evenly, creates the feeling of a larger space, and serves as the center of yurt life, providing warmth and food for more than half the year. As long as it’s airtight, a lightweight sheet steel stove is better than a more expensive fancy one with lots of thermal mass. Some of the best are the Tempwood stoves (made in Massachusetts but most easily found on Craigslist) and Four Dog stoves in Minnesota. A stove should heat up the yurt quickly when getting home at the end of a cold day. No one wants to wait around for hours shivering in boots and a coat.

When the yurt is up to your desired temperature, let the fire slowly purr along day and night. You’re heating air (not mass) and there is very little of that in a yurt. Heating thousands of cubic feet of space is entirely different than heating the tens of thousands of cubic feet commonly found in a typical American house. R-value, a measure of heat loss due to conduction, becomes relatively less important. And heat loss due to convection, as well as heat gain radiating from your woodstove, become key. After an April 2007 windstorm took the insulation off my yurt (note from experience: don’t ignore a loose flapping yurt panel for months on end) I spent the next year and half with no insulation. I noticed no difference in keeping the yurt warm. With a slow fire burning—hence the need for dry firewood, no creosote—and any drafts blocked up, I was toasty all winter. The first serious snowfall (around Christmas most years around here) adds additional natural insulation. By raking the snow off the roof before it melts, we create a warm layer of insulation all around the base of the yurt.

While there certainly are other types of fuel, I’ve never heard of anyone living through the winter here with anything other than a woodburning stove. Firewood is free, abundant, and simple—it’s the yurt dweller’s permacultural ideal.

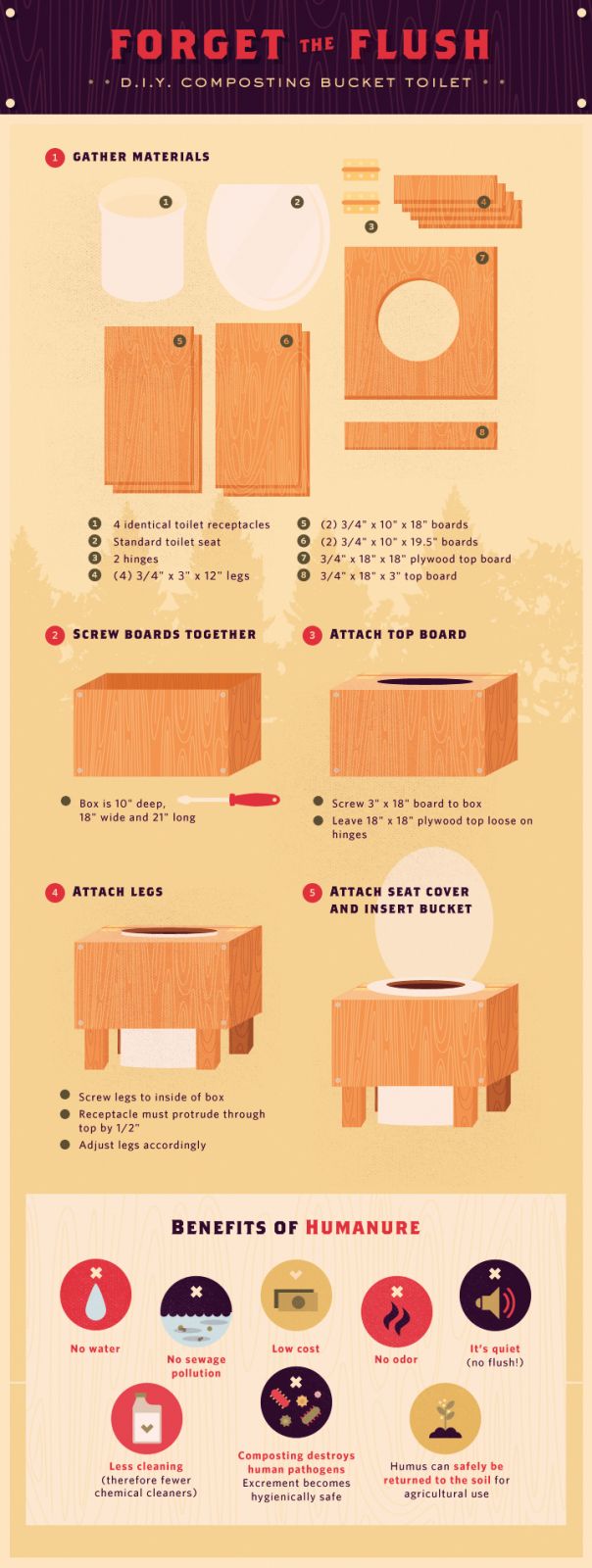

Plumbing: Bringing the Water Inside and Taking Care of Business Outside

So where do you go to the bathroom in a yurt? For us, the answer is in the humanure outhouse. Here’s a tip: Build it a little bigger than necessary (say, 6 feet by 8 feet) and it’ll become your attic, garage, and cellar, since the yurt lacks these. For more information on outhouses and composting poop, check out the Humanure Handbook by Joe Jenkins.

If heat and bathrooms are easy, the water question is anything but. Creating a system to deliver running hot water any time of day or year is the holy grail of the New England homestead system. Creating one that doesn’t freeze, leak, or get chewed through by beavers (please don’t ask) is even better. My answer is: Don’t create one, create two. In the summer, water stores easily. In the winter it is easily heated on the constantly-burning stove, but it will freeze if left out. I’m sure I’ve tried dozens of water systems and they all have pros and cons. Hauling buckets by yoke, sled, cart, car, or hand from springs, ponds, or the neighbor’s bathtub is simple. It does, however, get old (especially when washing cloth diapers by hand). Rainwater catchement systems off the yurt roof can provide lots of water (in summer, of course) for the dirty diaper task, but the water is too full of tree tannins and acid rain to drink or cook with. A garden hose run from a neighborhood spigot will work half of the year. It can even be hooked up to a sink in the yurt or an outdoor kitchen. Just remember to transition to your winter system before the first hard frost and don’t run the pipe through any beaver ponds.

Water regulations vary state by state. In New Hampshire, if the water is moving on its own accord into the yurt, a septic system and leach field are necessary. Beyond the question of wasting fertility (dishwater is full of phosphates that plants love) and giving possible pathogens a vector to spread in a giant tank of potable water, septic systems are very costly (more than the entire yurt). Plus, the look of a big sand mound just to accept the drinking water you’re polluting may not be worth it. Connect a pipe from the bottom of your dry sink, out the bottom of the yurt at the side, and into a patch of weeds or mulch. Don’t include a trap anywhere because it will freeze in winter and isn’t necessary.

Electricity: Amping Up the Yurt (Just a Little)

All the important needs—except refrigeration—can be accomplished with a tiny photovoltaic system or a very long extension cord. You can run a low amperage system hundreds of yards with very tiny wire if you start with this useful tidbit: Voltage drop is proportional to distance run. The traditional yurt refrigerator is the styrofoam cooler with half-gallon plastic jugs of ice swapped out every other day into the neighbor’s chest freezer. The next step up is a propane fridge. Running a small, energy efficient DC fridge (powered by solar) requires a medium-sized photovoltaic system, which is no small cost.

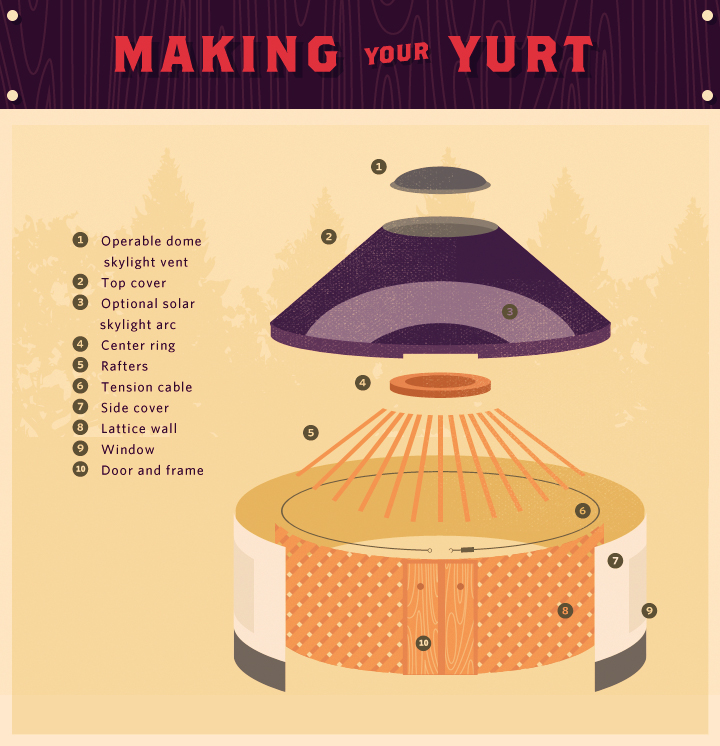

Building: Making Your Yurt

The Frame

Most yurt frames are built from sawn wood. When I created my first yurt I couldn’t afford to buy lumber, but had a small axe and access to a woodlot. I set out to craft the rafters and lattice wall from small-diameter saplings, which I continue to do to this day. The wiggly unmilled wood makes each yurt unique. Because the local hardwoods I use are very strong, I don’t have to reinforce my frames for snow.

Typically, a year-round yurt is set on a wooden platform. This platform does not need to be built on a frost-proof foundation. If there is not too much of a slope, it can be set on blocks, which rest directly on the ground. My favorite way to build the substructure of carry beams and joists is with green rough-sawn Eastern hemlock from a local sawmill. It is natural, renewable, plentiful (therefore inexpensive), super strong, and moderately rot-proof. Kept eight to twelve inches off the ground, not over a wet area, and it will last for decades. Pressure-treated wood is a more conventional way to go, but it fails the local and natural tests for me. Kiln-dried lumber fails most of my criteria as well.

The Floor

A yurt floor can be built beautifully from reclaimed wood. If one-inch boards are put down two layers thick over joists placed every two feet, the floor will be plenty strong and stiff. Installing a quarter-inch layer of foil-faced bubblewrap type insulation—or even just some 4-mil poly—in between layers will keep out the draft. Personally, I like 2×6 tongue-and-groove for strength and airtightness in a single layer. With regard to insulation, the key is to stop drafts from coming through the floor. Heat rises, so put more energy into insulating above you than below. One last thing: Don’t build the floor bigger than the circle of the yurt, or you’ll be looking at indoor rivulets every time it rains.

The Roof and Cover

In an ideal world, I’d always build yurts out of natural, local, ethical, nontoxic, low-carbon footprinted, renewable, long-lasting, beautiful, inexpensive, and functional materials. For the cover, functionality means keeping out weather, keeping in heat, resisting UV breakdown, and resisting flame. To get all these qualities is impossible, so I compromise. While slate makes just about the perfect roof, there goes the portability factor. Canvas is probably the most natural, beautiful, inexpensive yurt material, but it fails most of the other criteria. Even treated to resist UV, mildew, moisture, and flame, canvas will begin to deteriorate after three years if left up year-round. In New England, vinyl is a better option in many ways, and will last 10 to 20 years depending on the type. Some yurts are covered with used or unprinted billboard vinyl, which is fairly inexpensive and watertight for roughly five years if not moved in the cold (it cracks) or exposed to sparks (it burns). The final consideration for a cover is breathability. Canvas breathes and so do some woven vinyls, but most laminated fabrics do not. So long as you don’t pair a non-breathable outer cover with a breathable inner layer, you won’t have to contend with condensation.

Rules and Regulations: Building to Code

While water regulations tend to be statewide, building codes are usually enforced town-by-town. Codes may cover size restrictions, insulation, roof strength, fire rating, wind loads, and many more areas. Each yurt owner’s experience getting a structure permitted can vary widely. The good news is few municipalities tax temporary portable structures, including yurts. The bad news is that most building inspectors have never even heard of one. For a thorough discussion on yurts and building codes, check out the late Becky Kemery’s site, YurtInfo.org.

Life After the Yurt

After nine years of yurt living I was ready to move into a house. Fitting square furniture into a round space is a geometrical challenge. But, I miss hearing the skeins of geese migrate by starlight. And now that we’re in a house, the coyotes can break in to the chicken coop at night without me hearing a thing.

Ken Gagnon

Ken Gagnon lives and homesteads on fifty acres in rural southwest New Hampshire. He lived in one of his yurts for nine years. When not otherwise making music or art, he and his friends build places that feel nice to be in. His yurts are all framed with round saplings from the forest, hand built and sewn on his homestead, and delivered and set up by him around northern New England. To learn more about his yurts and timberframes, or what happens at Two Girls (they’re his daughters, for the record, one of whom was born in a yurt) Farm, check out twogirlsfarm.org.